Japan

Not quite so invincible

Some of Shinzo Abe’s shine comes off

Jul 19th 2014 | TOKYO | From the print edition Economist

THE mood until now in Japan’s longest-serving cabinet in memory has been one of swelling self-assurance. After all, nearly everything has gone right for Shinzo Abe, the prime minister—from his own restored health to his ministers’ avoidance of Japanese politicians’ habitual gaffes and scandals. Yet the ruling party’s defeat in an election for governor of Shiga prefecture on July 13th has unnerved the government. Meanwhile, Mr Abe’s advisers are also scrambling to explain why his once-unassailable approval ratings have fallen in national opinion polls, to below 50% for the first time.

The two setbacks are related, and probably have to do with the way in which Mr Abe is perceived to have forced through a historic change in Japan’s security policy against the will of most of the public. This month the cabinet approved a reinterpretation of the pacifist constitution to allow a limited right of “collective self-defence”. Japan’s armed forces will be allowed to come to the aid of allies should the nation’s security be threatened.

Given voters’ caution over security, the shift to embrace collective self-defence was bound to use up some of the prime minister’s political capital. Many criticised the government for seeking to make the change through the (usual if rather shabby) fudge of a reinterpretation of the constitution rather than the much harder route of a full revision. Mr Abe has hardly helped his case with his ultranationalist views on history, generating outrage among neighbours and an amount of unease at home.

Lastly many Japanese disapproved of Mr Abe’s apparent bullying of his pacifist coalition partner, New Komeito, into backing the change on collective self-defence. New Komeito relies for its support on Soka Gakkai, a lay Buddhist group with several million members. These, especially the women, are a local electoral force channelling votes both to New Komeito and to Mr Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The bullying backfired. In Shiga fewer Soka Gakkai members turned out to canvass or vote for the LDP’s candidate. Takashi Koyari had been expected to win handily, but a former lawmaker from the opposition Democratic Party of Japan, Taizo Mikazuki, narrowly defeated him.

The LDP’s defeat may presage further headaches for Mr Abe. Mr Mikazuki campaigned on an anti-nuclear platform, a potent theme in Shiga: voters feared the approaching restart of reactors just over the prefectural border in Fukui. This week Japan’s nuclear watchdog approved the restart of two reactors in Kagoshima prefecture on the southern island of Kyushu, the first to receive the go-ahead after a countrywide shutdown following the Fukushima disaster in 2011. Some of Fukui’s reactors are expected to receive the nod, perhaps later this year. Around the country, opposition to switching on nuclear plants is only growing.

Mr Abe’s policies on national security and on nuclear power are turning off women especially. That accounts for much of the drop in the polls, one of his advisers says. It can hardly have helped that a misogynist LDP member of the Tokyo local assembly recently heckled a fellow-member, telling her to hurry up and get married.

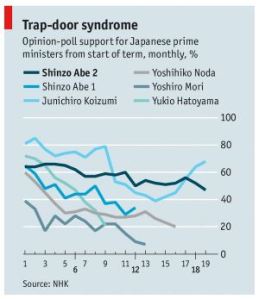

Can Mr Abe get his shine back? He is still doing better than most previous prime ministers (see chart).

Other local elections are due this autumn in Fukushima prefecture, home of the tsunami-stricken plant, and in Okinawa, a Soka Gakkai stronghold that bears the brunt of the American troop presence. Should these also prove setbacks for the ruling party, the chances of Mr Abe pushing through his economic plans may be weakened. For the time being, the adviser says, Mr Abe is shifting his attention back to economic matters and other livelihood themes on which voters want him to concentrate.

However much the economy matters, the government’s spin doctors know that Mr Abe would enjoy a real surge in popularity should he secure the return of at least some of 17 or more Japanese nationals who decades ago were kidnapped by North Korea. In May Japan reached an agreement with North Korea to relax sanctions on the pariah regime in return for a new investigation into the fate of its abducted citizens. In 2002 the same gambit rescued the ratings of Junichiro Koizumi, Mr Abe’s mentor, which had plummeted after the sacking of a popular minister. If Mr Abe can bring home Megumi Yokota, a national totem whom North Korean frogmen seized in 1977 when she was 13 and who may or may not be alive, then he would become unassailable. But it is hardly wise to rely for political succour on the world’s worst—and least co-operative—regime.